VENERI: to VENUS

Colourized image of the Venus of Arles, one of the most famous depictions of Venus ever discovered in Gaul.This image is based on an early plaster copy in the Musée de l’Arles Antique. This copy is actually more faithful to the original appeareance than the infelicitously restored statue in the Louvre.

(Musée de l’Arles Antique)

Sculpture of Venus with a dolphin, indicating her maritime affinities. Note the voluptuous suppleness of the figure. This is probably a Gallo-Roman work, found at Pourrières in the département of the Var.

(Musée Lapidaire d’Avignon)

Venus received a warm welcome among the Gauls. To be sure, she never attained the rank of the most vaunted gods in Gaul, and she does not seem to have had a Celtic precursor (at least, we find no Celtic epithets attributed to her). Under the Roman Empire, however, she was everywhere. She frequently appeared on Jupiter columns; inscriptions honoured her quite frequently; her image became a favourite motif in the homes of the leisured class. On the other hand, her representations in terracotta or other inexpensive materials are what show her to have been one of the most popular deities in Gaul. Humble though her worshippers might be, they sought all the more ardently after the indespendable aid of the goddess.

Venus’ essential function is to preside over love—including phyiscal attraction, sexuality and even adulterous affairs. Herein lies the chief point of contention between Venus and Juno, protector of the inviolable institution of marriage who appears moreover as Venus’ constant antagonist in the Æneid, Iliad and other texts. Venus’ entourage naturally includes Cupid, her son and assistant, but also Priapus (the ithyphallic god who governs virility) and at times Mars. Today, as in ancient times, sexuality tends to be identified with the image of woman as object of sexual desire; so it is that Venus representes, first and foremost, the charms, the beauty and the allure of the female sex.

Venus is ordinarily represented nude (an artistic innovation introduced by Praxiteles, but quite established by the time of the Gallic Wars). Among her attributes are a mirror, the Apple of Discord (which Venus was awarded by Paris, indirectly provoking the Trojan War), the girdle, the dove, the swan, the hare and the myrtle. Born at Cytherea from the sea, which (according to one version of the myth) had been inseminated by the sea-foam issuing from the severed phallus of Uranus, she frequently appears with sea-shells and marine creatures such as dolphins.

At Rome, feast days in honour of Venus include the 18 August (Vinalia Rustica, inauguration date of the oldest temple of Venus in Rome), the 1 April (Veneralia) and the 23 April (feast of Venus of Eryx).

Love Affairs of the Goddess of Love

Venus inherited the same amorous temperament as her father Jupiter, if the poets are to be believed. As early as the 7th century BCE, the Hymns called Homeric (thanks to their style and meter) dedicate a long section to the amour of Venus and Anchises, from which Æneas was born.

Still, the most famous lovers of Venus are Mars and Adonis. In both cases, the poet who gives them the best literary treatment is Ovid. In one comic episode, Vulcan booby-traps his wife Venus’ bed; when Mars and Venus are caught in it, the smith-god invites the Olympians to come laugh at the spectacle.P. Ovidivs Naso, Metamorphoseon iv. The myth of Adonis is more serious. The lover is mortal; as Ovid tells the story, he dies while boar-hunting. Venus, beside herself with grief, transforms him into an anemone and institutes a commemoration which women observed each year by keening from the roof-tops.P. Ovidivs Naso, Metamorphoseon x.

Venus’ husband, however, is Vulcan. Ugly and lame, he is nevertheless secure, capable and masculine. The poets indicate that, despite one spouse’s infidelities and the other’s jealousies, the couple were able all in all to forge an agreeable modus vivendi.

Bronze statuette of a winged Cupid, found at Lyon.

(Musée de la Civilisation Gallo-Romaine, Lyon)

A charming terracotta statuette of Cupid and Psyche from Cologne, found at Tongres in the Belgian province of Limburg.

(Gallo-Romeins Museum, Tongeren)

Cupid

Horace calls Venus the mater cupidinum, mother of desires or love affairs,Q. Horativs Flaccvs, Carmina i: 19. and for this reason the god Amor (Cupid) is considered the son of Venus. His paternity (appropriately enough!) is disputed. He is normally winged—at least from the time of Apuleius—and bears the arrows that make gods and mortals fall in love. He is depicted as either a child or an adult. The former motif carries on in the cupids and cherubs of modern art. The latter is chiefly found in connection with the lovely myth of Cupid and Pysche, retold by Apuleius,L. Apvleivs Madavrensis, Asinus aureus siue Metamorphoses iv.28–vi.25. which symbolizes the good and ill effects of Love upon the Soul (known in Greek as Ψυχή or psyche). Both motifs were as popular in Antiquity as they are in modern times (one need only mention the sublime works of Canova, Rodin, Bouguereau and others on this theme).

The Graces

Three other goddesses in Venus’ entourage are the Graces: Euphrosyne (joy), Thalia (plenty) and Aglaë (splendour). As a trio (and from the time of Hesiod, they have hardly ever been conceived otherwise), they represent vivacity—a full and joyful life. In Gaul, they do not seem to have been objects of worship, but they do appear on mosaics and other decorative elements (much as paintings and sculptures of the Three Graces have had a certain vogue since the Renaissance).

Gallery

Bust of Venus found at Cologne: Roman copy of a work by Praxiteles.

(Römisch-Germanisches Museum, Cologne)

Terracotta statuette of a clothed Venus.

(Musée Saint-Remi, Reims)

Nude Venus emerging from the sea. This was a terracotta plaque that one might hang up in a domestic shrine. This type of production is a typical indicator of the cult of Venus among common people.

(Musée Roulin, Autun)

Terracotta statuete of Venus.

(Musée de la Civilisation Gallo-Romaine, Lyon)

Bronze statue of Venus with the Apple of Discord.

(Römisch-Germanisches Museum, Cologne)

Venus Genitrix

Venus had a particular significance for the Julio-Claudian house, for the gens Julia claimed descent from Iulus, which is to say Ascanius, son of Æneas. Now, Æneas was the son of Venus and the mortal Anchises. While Julius Cæsar enjoyed political supremacy, the dictator promoted the worship of Venus Genitrix, that is, Venus the progenitor of the Roman people—and more directly of his own lineage. The mythology of Æneas as forefather of the Romans—already widely accepted—was immortalized in Virgil’s Æneid, composed during the principate of Augustus.

Venus Genitrix is one of the goddess’s victory-bearing manifestations, much like Venus Victrix (Victorious Venus) favoured by Pompey (this was a Latinization of Aphrodite Nicephora), the Venus Felix (the Fortunate Venus) worshipped by Sulla, and the Venus Erycina (Venus of Eryx) credited with victory against the Carthaginians in 215 BCE. The role of Venus could thus extend, in extreme cases, to the military protection of the commonwealth whose foundations she had laid through her illustrious son Æneas.

The Heavenly Venus

Philosophers favoured rather the ‘Heavenly Venus’ (Aphrodite Urania), who presides over spiritual love.

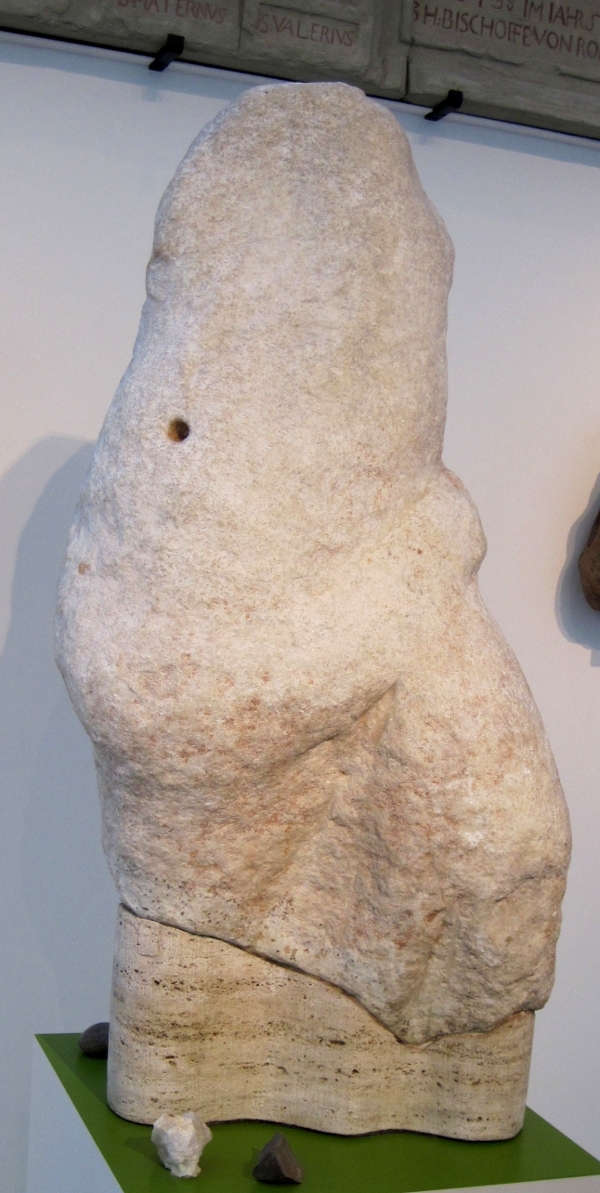

Mediæval fanaticism, rather than weathering, has reduced this objet d’art and cult statue into an amorphous block.

(Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Trier)

A Case of Christian Ritual Sacrilege

A sculpture of Venus at Trier, in the monastery of Saint Matthias, received ongoing ritual attention during the Middle Ages. Each year during Holy Week, the crowd would gather to hurl stones at the offending ‘idol’. Might the cult of Venus—feminine, sexualized, worldly—have in some wise been recognized as a potent antithesis of Christianity? The physical effects of this practice, at any rate, are plain. A marble statue of the Venus Anadyomene type (that is, Venus drying her hair as she rises out of the sea) was reduced back into crude and shapeless stone.Eberhard Sauer (1996), The end of paganism in the north-western provinces of the Roman Empire, p. 92. May we not take this as a fitting symbol of the cultures of paganism and Christianity, and their respective fruits?

Notes

En français svp !

Auf deutsch, bitte!