EPONAE: to EPONA

Coloured image of Epona riding side-saddle. She carries a basket of fruits.

(After a relief from Dalheim now in the Musée national d’histoire et d’archéologie, Luxembourg)

“Epona: she is the goddess who concerns herself with the protection of horses”

— Pseudo-PlutarchPseudo-Plutarch, Parallela Minora 29. The author gives a very brief summary of Epona’s birth from Fulvius Stellus and a mare, citing the authority of Agesilaüs. The identity of this Fulvius Stellus is not explained here, and as far as I know it is the only attestation. Original version:

Φουλούιος Στέλλος μισῶν γυναῖκας ἵππωι συνεμίσγετο, ἡ δὲ κατὰ χρόνον ἔτεκε κόρην εὐμορφον, καὶ ὠνόμασεν ῎Εποναν. ἔστι δὲ θεὸς πρόνοιαν ποιουμένη ἵππων, ὡς ᾽Αγησίλαος ἐν τρίτωι ᾽Ιταλικῶν.

“Hating women, Fulvius Stellus used to join with a mare; in due course, the mare gave birth to a beautiful girl called Epona: she is the goddess who concerns herself with the protection of horses. So (writes) Agesilaüs in the third (book) of his History of the Italic Peoples.”

Epona is before all else the horse-goddess of the Gauls. This assertion is confirmed by the goddess’s iconography (she is almost obligatorily depicted with one or more equines), by the etymology of her name, and by what little we know of her mythology. Epona was the Celtic goddess who gained the most success among the Romans. She was much worshipped by the Gaulish cavalry, whom the Romans greatly admired, and which was made up of the cream of the native aristocracy. The descendants of this equestrian élite later contributed to make up a prestigious unit of the Roman army, the Equites Singulares Augusti or ‘Emperor’s Own Horse-Guard’. As it happened, these Equites Singulares Augusti played a major role in spreading the worship of Epona, whom they continued to venerate in the city of Rome as in the provinces. Her cult continued to spread, reaching even the most humble stables of Greece by the 2nd century CE.This at least is what is found by Lucius, the protagonist of Apvleivs’ novel the Metamorphoses. Lucius has here been transformed into a donkey—a perspective that allows him unfettered access to the religious customs prevailing in the stables of his era.

The goddess’s name means simply ‘the great mare’; it is based on the same Gaulish root as epos ‘horse’ (cf. Latin equus and Greek ἵππος hippos).Xavier Delamarre (2003), Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise, p. 163. ,One of the months of the Coligny calendar is named Equos. This, however, is probably a red herring with respect to Epona, as the month of Equos would more likely derive from a root ecu- ‘cattle’ (from Proto-Indo-European *péku), a suggestion put forward by Delamarre (2003), p. 164. To this is added the same augmentative suffix -on, also found in Ritona ‘the great ford’, Ðirona ‘the great star’, Maponos ‘the great son’, etc.

Description of the goddess

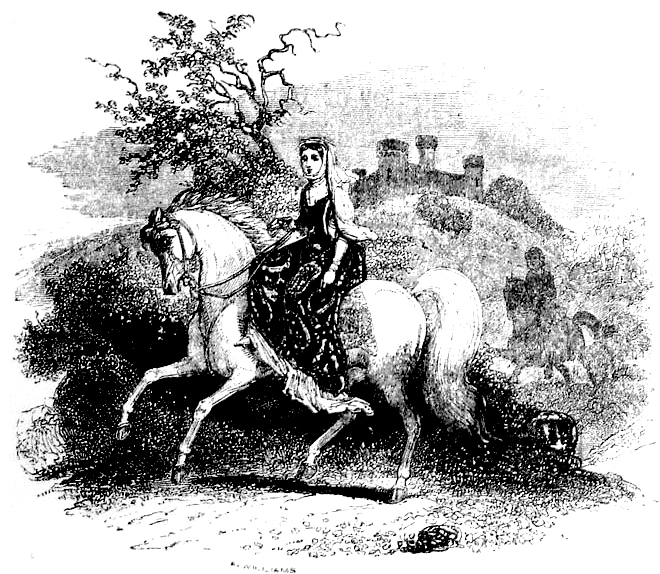

Epona is most often depicted riding side-saddle. Often she touches her steed’s mane (it is normally a mare) with her left hand, in which she may alternatively hold a cornucopia. In her right hand she holds a patera (a ritual offering dish) or a basket of fruits or loaves. A foal sometimes accompanies the mare, particularly in the Æduan country. This is what Nantonos Aedui and Ceffyl, the authors of the excellent site epona.net, define as the “sidesaddle type”, which is the most widespread in Gaul. Another common type, called the “imperial type”, shows Epona sitting upon a throne flanked on both sides by two or even four equines, which she typically feeds from the basket on her lap. The imperial type is most often seen outside of Gaul.Nantonos & Ceffyl (2004–2007), “Depictions of Epona”, Epona.net.

Epona’s attributes (a basket of fruit, cornucopia, and/or patera) can also be found with other deities, such as the Lares, the Matronæ, Nehalennia, and Abundantia. They are canonically symbols of prosperity, fertility, and (in the case of the patera) piety. The only really distinctive characteristic of Epona is the presence of one or more equinesMiranda Green (1989), Symbol & Image in Celtic Religious Art, p. 5.—but this is enough to delineate a number of the roles the goddess fulfils.

For instance, a number of circumstances point to a connection between Epona and the Otherworld. Some elements of her iconography that have been interpreted this way are capable of alternate interpretations (such as the occasional depiction of a key or a raven); however, the presence of reliefs of Epona in funerary contexts seems decisive.Miranda Green (1989), Symbol & Image in Celtic Religious Art, pp. 18–19. Does Epona, the divine rider, lead the soul of the departed to its new home, thus acting as psychopomp? It may be remarked that the role of psychopomp, so often reserved for Mercury in Roman contexts (and still more for Hermes in Greek ones), barely registers as an important characteristic of the Gaulish Mercury. Might the latter delegate to his equestrian colleague the role of psychopomp in Gaul, where as “the god whom [the Gauls] worship the most”C. Iulius Caesar (summarizing Posidonius), De Bello Gallico vi: 17. he has so many other responsibilities?

In Apuleius’ novel The Metamorphoses, Epona—while goddess of horses—also appears as the protector of donkeys. This is a detail of no passing importance for Lucius, the protagonist, who has been transformed into a donkey by a magical mishap. The Christian polemicist Minucius Felix seems to confirm that donkeys are under Epona’s protection,“...unless you (pagans) consecrate donkeys whole in your stable with your Epona...”. M. Minvcivs Felix, Octauius 28. while a scholia on Juvenal’s Satires also identifies her as “goddess of muleteers”.Collection of Divers scholies et gloses after Zwicker (1934), cited by Guillaume Roussel (1999, 2018), Inventaire des textes anciens / Epona, L’arbre celtique.

Epona is sometimes depicted at a healing spring site, as at Sainte-Fontaine near Freyming-Merlebach in modern Alsace, or at Allerey in the territory of the Ædui.Miranda Green (1989), Symbol & Image in Celtic Religious Art, pp. 17–18. Might this reflect a journey (on horseback) used as a metaphor for the healing process?

Epona of the “imperial type” on a stele from Salonica, Macedonia. The enthroned goddess is surrounded by four horses. (Salonica Archæological Museum)

Characteristics of her worship

“I fortuned to espy in the middle of a pillar sustaining the rafters of the stable the image of the goddesse Epona, which was garnished and decked round about with faire and fresh roses.”

— ApuleiusApvleivs (2nd century), Metamorphoses III: 27. In this 16th-century translation by William Adlington, the goddess’s name appears as ‘Hippone’—rather a pleasant-sounding anglicization—but I have restored the original ‘Epona’ for consistency’s sake. Original version:

respicio pilae mediae, quae stabuli trabes sustinebat, in ipso fere meditullio Eponae deae simulacrum residens aediculae, quod accurate corollis roseis equidem recentibus fuerat ornatum.

The stables were doubtless the scene of the most humble worship of Epona. Here was an entire human industry who might have reason to deal with the horse-riding goddess: teamsters, coachmen, grooms, ostlers, breeders, even farriers, saddlers, and cartwrights—professions whose very names are now fading from memory—no less than the knights and squires belonging to a wealthier class. The professionals of such lines of work undoubtedly helped introduce the cult of Epona into certain regions of the Roman Empire (such as Greece, perhaps). We may picture pious gifts of flowers or other small offerings such as Apuleius describes in countless stables in many regions. The poet Prudentius attests to offerings of incense and ground meal to Epona and refers to inspecting the entrails of sacrificial victims for purposes of divination.Both Cloacina (goddess of sewers) and Epona are said to have received such offerings. Aurelius Prvdentivs Clemens (4th century CE), Apotheosis siue Hymnus de trinitate, ll. 197–199. These are merely the standard conventional offerings of Roman religion writ large (the real target of the poet’s condemnation). The ground meal (mola) probably refers to salted spelt-meal (mola salsa) which was used as a simple offering or sprinkled on the head of an animal to purify it for sacrifice (this is the original meaning of the word ‘immolate’).

However, Epona’s association with the stable created an impression, at least for some, that Epona herself was a goddess of the lowly and repulsive. Juvenal denounces one haughty aristocrat whom he accuses of swearing not by Jupiter but by Epona, whom the satirist considers a gross or even filthy deity, fit only for the stables.D. Iunius Ivvenalis (from 100 to 127 CE), Saturae III.8.155–157.

This is but one of numerous faults for which Juvenal attacks this errant grandee, and as usual, our satirist goes in with all guns blazing, heedless of any collateral damage.

Some centuries later, the Christian poet Prudentius appears to class Epona with Cloacina, the Roman goddess of sewers, as unworthy of worship or of a place in heaven.Aurelius Prvdentivs Clemens (4th century CE), Apotheosis siue Hymnus de trinitate, ll. 197–199.

The late antiquarian Fulgentius cites Epona as an example of a semo or earthly deity, on the same basis as Priapus or Vertumnus, who like her are “not worthy of heaven”.

Fabius Fvlgentivs (c. 600 CE),

“Expositio Sermonum Antiquorum” 11.

Original version:

[Quid sint semones.] Semones dici uoluerunt deos quos nec caelo dignos ascriberent ob meriti paupertatem, sicut sunt Priapus, Epona, Vertumnus, nec terrenos eos deputare uellent pro gratiae ueneratione, sicut Varro in mistagogorum libro ait: “Semoneque inferius derelicto deum depinnato orationis attollam alloquio”.

There was thus a persistent habit of relegating Epona to the stable alone, where she was tasked with overseeing the most uncouth operations. We only see this habit, however, among Italians and Africans who did not themselves worship her.

Depiction of Epona at Scarponna, now Dieulouard in the country of the Mediomatrici. The goddess is riding side-saddle and carrying a basket of fruits; here, the mare is nursing a foal.

(Drawing of a stele that is now lost. Espérandieu no 4605)

In other regions, however, there is plentiful evidence that people continued to hold this goddess of the Celtic nobility in high esteem. Several inscriptions, notably those from the Balkans and the Danube, hail her as Epona Regina (‘Queen Epona’)In Dacia: CIL iii: 7750 (Alba Iulia / Apulum); in Dalmatia: Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL) iii: 12679 and Année Épigraphique (AÉ) 1933: 76 (Duklja); in Pannonia: RIU iii: 869 (Aquincum). or, more frequently still, as Epona Augusta.In Dacia: AÉ 1937: 184 (Alba Iulia / Apulum); in Noricum: CIL iii: 5176 (Celeia), CIL iii: 4776 et CIL iii: 4784 (Virunum), CIL iii: 5312 (Maribor); in Pannonia: CIL iii: 3420 (Aquincum). Often in Gaul an evocation of Epona or dea Epona is preceded by a formula referring to the imperial cult, either In · H · D · D ‘in honour of the divine house’ or Aug · Sac ‘sacred to the Augustus’ depending on the region and era. The consecration of an altar to Epona and the genius of the Leuci at Nasium (Naix-au-Forge in modern Lorraine)CIL xiii: 4630. might also emphasize the link between Epona and the local nation. Thus, the association between the sovereignty of the land and the sacred horse does not seem to have been forgotten in these provinces of the Empire—nor among the Emperor’s Own Horse-Guard, who were among the chief worshippers of Epona in Rome. An atavistic concept said to date back to the Indo-Europeans, the renewal of sovereignty by the sacrifice of a horse has been argued to underlie the Irish sacrifice of a white mare on the inauguration of a new king,Giraldvs Cambrensis (c. 1188), Topographia Hibernica 25. This practice was said in the 12th century to be limited to the remote county of Tyrconnel (Donegal). the Vedic rite of the ashvamedha, and the annual Roman sacrifice of a horse to Mars (Equus October).Georges Dumézil (1970), Archaic Roman Religion, pp. 224–228. However this may be, some of Epona’s worshippers certainly recognized in her a queenly power.

The presence of monuments to Epona in the Greek-speaking and Danubian provinces and in Rome itself, as well as Britain and Spain, give some indication of the cult’s geographical reach. At the same time, it should not be forgotten that the worship of Epona was at its most intense in Gaul, and in particular in eastern and northern Gaul. Inscriptions and depictions of Epona cluster in the lands of the Ædui, Mediomatrici (notably in Metz), and Treveri (notably at Dalheim in Luxembourg and at Trier), with significant overflow to the east into Upper Germany and to the west in Aquitania.Miranda Green (1989), Symbol & Image in Celtic Religious Art, pp. 16–17, 22.

While eastern Gaul was the epicentre of Epona’s worship, the provinces along the Danube became her second home. Dacia, Pannonia, Mœsia, Noricum, and Dalmatia—settled in part by several waves of Celtic peoples, and lands favoured like Gaul itself for cavalry recruitment—have yielded a good thirty inscriptions in honour of Epona, half of all those outside of Rome.

The date of 18 December has been identified as that of a feast-day of Epona. This much is attested from a fragmentary calendar from Guidizzolo in Venetia,AÉ 1892: 83. but it is not known how widely the holiday was celebrated in other places. It is remarkable in any case that Epona was the only Celtic deity endowed with a feast-day in any Roman calendar.Miranda Green (1989), Symbol & Image in Celtic Religious Art, p. 23. I would also like to draw attention to the dedication of an altar on 18 March of either 250 or 251 CE at Tilena (Til-Châtel in the Côte-d’Or); this altar was dedicated in H · D · D · deae Eponae dis Mairabus genio loci ‘in honour of the divine house, to the goddess Epona, to the Di Mairæ, and to the genius of the place’.CIL xiii: 5622. (The identity of the Mairæ is, I think, unclear; as dis ‘gods’ they are probably not to be identified with the Matronæ or mother-‘goddesses’, deabus.)

Epona’s entourage

I’ve just mentioned an inscription where Epona is evoked along with the obscure Di Mairæ and the genius loci. The epigraphic evidence shows a number of other noteworthy collocations between Epona and other deities (cf. the table assembled by Nantonos and Ceffyl on Epona.net). The most distinctive of these may be the Campestres, or “deities of the field”, who are evoked along with Epona by centurions in BritainThis is an altar dedicated to Mars, Minerva, the Campestres, Hercules, Epona, and Victoria near the Antonine Wall in modern Scotland. CIL vii: 1114. and Dacia,At Sarmizegetusa: CIL iii: 7904. by a cavalryman of the Equites Singulares Augusti in Rhætia,At Celeusum, now Pförring in Bavaria: CIL iii: 5910. and numerous times by the Equites Singulares Augusti in Rome.See my analysis of one such inscription. The field over which the Campestres preside is thought to be the training ground rather than the battlefield.Georgia L. Irby-Massie (1996), “The Roman Army and the Cult of the Campestres”, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 113, pp. 293–300. The writer construes the word Campestres as feminine and likens the Campestres to the Valkyries, on the look-out for warriors who have proved themselves ready for battle.

The inscriptions of the Equites Singulares Augusti in Rome typically evoke virtually a whole pantheon of gods and goddesses honoured by these cavalrymen, including Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva (the Capitoline Triad); Mars and Victoria; Mercury, Felicitas, Salus, the Fates, the Campestres (as we have just seen); Silvanus, Apollo, and Diana; Epona, the Matres, the Suleviæ (unless this is instead an evocation of the “Matres Suleviæ”), and the genius of their regiment. While the Equites Singulares Augusti were certainly assiduous in their devotions to Epona, this is seen primarily in contexts where numerous other deities were honoured as well.

Stele of Epona found at Gannat (Auvergne). She carries a large key (a key to the stable? or to the Otherworld?). Her cloak waves around her in a “nimbus”, recalling the traditional depiction of Europa on the back of the bull.Miranda Green (1989), Symbol & Image in Celtic Religious Art, pp. 16, 18.

(Espérandieu no 1618)

As a rule, the multi-deity dedications of the Equites Singulares Augusti begin by evoking Jupiter. Co-dedications to Jupiter Optimus Maximus and Epona are often to be met with in Dalmatia and Noricum.CIL iii: 5192, 8671, 12 679; AÉ 1933: 76. Perhaps a vanished myth told of a liaison between Epona and the amorous Jupiter—or, if not, the allusion would be sufficiently explained by the way their roles complement each other, for Epona reigns over the land, one might say, as Jupiter does over the skies.

One inscription attests a shrine in Rome dedicated to the very interesting trio of Hercules, Epona, and Silvanus.CIL vi: 293. All three can be seen in one respect or other as champions of the underdog. All are also popular in an area north of the Alps (stretching from Gallia Belgica and Upper Germany through Rhætia and Noricum to Pannonia), and all three deities are among those regularly evoked by the Equites Singulares Augusti. There is also an altar dedicated to Hercules and Epona Augusta in Noricum for the salvation of the emperor.The emperor in question was Bassianus (Caracalla), who could well have benefited from salvation... CIL iii: 4784.

I’ve already mentioned the allusion to Epona in Apuleius’ comic novel, The Metamorphoses. Here, Epona furnishes a kind of link to Isis. Lucius, transformed into a donkey, first seeks deliverance from Epona; he finds it, after many (mis)adventures, with Isis. Still, any Epona–Isis nexus that might be inferred from Apuleius is by no means an exclusive one, for the same author has Isis declare her absolute identity with quite a number of other goddesses.Namely (in Adlington’s translation): “my divinity is adored throughout all the world in divers manners, in variable customes and in many names, for the Phrygians call me the mother of the Gods: the Athenians, Minerva: the Cyprians, Venus: the Candians, Diana: the Sicilians Proserpina: the Eleusians, Ceres: some Juno, other Bellona, other Hecate: and principally the Æthiopians which dwell in the Orient, and the Ægyptians which are excellent in all kind of ancient doctrine, and by their proper ceremonies accustome to worship mee, doe call mee Queene Isis.” L. Apvleivs, Metamorphoseon XI.5. But since the Christian polemicist Minucius Felix also refers to Isis and Epona together,M. Minvcivs Felix, Octauius 28. perhaps they were associated in people’s minds somewhat more regularly—if only as deities who shared a non-Roman identity (much like Jesus Christ, in the view of this Father of the Church). The context here doesn’t permit any more detailed conclusions.

In his brief euhemeristic reference, pseudo-Plutarch may possibly preserve the echo of an Italic legend in which Epona was fathered by a certain Fulvius Stellus.Pseudo-Plutarque, Parallela Minora 29; see note above for the full text. Might the Italic peoples have invented such a myth after receiving this goddess of undoubtedly Celtic origins into their midst? In such a case, would this Fulvius Stellus be a man, a demigod, or even a semo or local deity? While the gens Fuluia was indeed a well-known plebeian clan, According to Cicero and Pliny, the gens originated around Tusculum in Latium. “Fulvia Gens” in William Smith (éd., 1849), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. “Stellus” does not figure in Roman naming practices and can only be a reference to a star, stella (which perhaps fell to earth in Latium as a meteor to give its name to Epona’s supposed father?—but perhaps I have my head in the clouds on this one).

Epona shares with Mercury a certain responsibility over travellers, material prosperity, and passage into the Otherworld. Nantonos and Ceffyl draw attention to a stele from Strasbourg where Mercury is flanked by two (!) depictions of Epona. Certain inscriptions (notably those of the Equites Singulares Augusti) evoke Epona together with Mercury or Hermes,Nantonos & Ceffyl (2004–2007), ‘Deities Associated with Epona’, Epona.net. but all in all their association seems less pronounced than one might have expected.

Epona is not the only Gaulish deity with strong equine associations. In addition to gods who are sometimes depicted on horseback (such as Jupiter riding down a giant, or Castor et Pollux), there is a god named the “august Rudiobus” to whom an elegant bronze statuette of a stallion was dedicated at Neuvy-en-SulliasMonique Dondin-Payre. « Celtiques ? Romains ? Indigènes ? Importés ? Divinités et pratiques religieuses dans l’empire romain de l’Occident. » Pages 76, 81, 86 and 91 in Marie-Odile Charles-Laforge (2014). Les religions dans le monde romain: Cultes locaux et dieux romains en Gaule de la fin de la République au IIIe siècle après J.-C. : persistance ou interpretatio ? Artois Presses Université. in the territory of the Carnutes (perhaps a depiction of the god himself?).

Counterparts in the Isles

Elsewhere I have stated my reservations about the formerly rampant tendency to drown Gaulish religion in a pan-Celticism essentially defined by Irish mythology (and to a lesser extent by Welsh mythology). While Irish mythology is obviously vivid and stirring, several centuries, great distances, and clear cultural divergences separate it from Gallo-Roman religion. In the case of Epona, however, we encounter mythological figures whose analogies with Epona seem rather apt than forced; Nantonos & Ceffyl (2004–2007), “Later influences of Epona”, Epona.net. what’s more, Epona’s nearly pan-Celtic distribution (an almost unique case) strengthens the hypothesis that Epona’s myths might have found echoes in the traditional tales of Ireland and Great Britain. I’m therefore dedicating this section of the page to the Irish Macha and the Welsh Rhiannon. Macha is frequently identified with the Morrígan, whose name, like that of Rhiannon, derives from the Celtic root rigani ‘queen’, which brings to mind the Romano-Celtic evocations of Epona Regina.Patrick K. Ford (1977), “Introduction”, The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales, p. 5.

Macha

The principal mound of Emain Macha, site of the ancient capital of Ulster founded by the legendary high queen Macha Mong Ruad.

(Modification of a photo by Jon Sullivan in the public domain)

Macha is an Irish goddess whose legends connect her on the one hand with the Morrígan and on the other with the city of Emain Macha, the ritual capital of the kingdom of Ulster. The Morrígan is, to simplify matters, a warrior-goddess consisting of three persons (typically Morrígan, Badb or Badb Catha, and Macha, but the list can vary). Her name mor-rígan means ‘great queen’. She chooses the victors in battle; she attacks heroes or seduces them, at her will. The Christian monks who passed Irish mythology down to us evidently found in her a sinister but fascinating character.

The myths of Emain Macha and Ard MachaEmain Macha, today Navan Fort or Eamhain Mhacha ou Navan Fort, is an archæological site a few kilometres from the hills of Ard Macha. The urban centre is now to be found on the latter hills; called Armagh or Ard Mhacha, it has been the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland from the time of Patrick. are complex: they feature a series of supernatural figures who, from age to age, are all named ‘Macha’ and whose deeds result in the foundation of this capital city of Ulster (such is the accomplishment of Macha Mong Ruad, the High Queen of Ireland, who marked out the limits of the city with her brooch) and also a curse against the men of that province. This latter story is of particular interest. Several centuries after the foundation of the city, an Ulsterman who had married a woman of the shee (Macha) drunkenly boasts of his wife’s abilities, declaring that she could out-race the king’s best horses. The king accepts the challenge, promising to put to death the boastful husband (whose name is Crunn) if his wife does not race against the royal chariot. Macha, however, is at an advanced state of pregnancy. At first she refuses to take part in this race, then gives in with a very bad grace. She runs, she suffers, and at last she beats the king’s horses. Just after crossing the finish-line, she gives birth to a twin son and daughter. Naturally exhausted, she curses the men of Ulster, condemning them to suffer the pains of childbirth whenever their danger is greatest...This story appears as a preliminary episode (réamhscéala) to the Táin Bó Cúailgne, the so-called ‘Cattle-Raid of Cooley’, as well as in the Dinnsenchas (placename lore) of Armagh and/or Emain Macha, such as the Rennes Dinnsenchas 94, the Edinburgh Dinnsenchas 61, and the Metrical Dinnsenchas 112. This was to prove a considerable obstacle once the Cattle-Raid of Cooley began.

The persistent connections between Macha, horses, and/or kingship. Both of the legendary Machas I have describe (there are one or two others of lesser importance) gave their name to Ard Macha (Armagh) and to Emain Macha, a royal city. One of them is High Queen (like Epona who is queen or augusta), while the other confronts a king who is humiliating her. Her humiliation consists in being treated not with the dignity due to a pregnant woman but like a race-horse. Both legendary Machas might be avatars of the goddess Macha, who forms one person of the Morrígan, the ‘great queen’.

Rhiannon

Rhiannon, illustration in Lady Charlotte Guest’s translation (1877).

(Modification of an image in the public domain)

In Rhiannon’s case, there are still more resemblances with Epona. The name Rhiannon derives from *Rigantona, which is to say ‘great queen’.Xavier Delamarre (2003), Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise, p. 257. Rhiannon’s adventures are as complicated as they are romanticized; they span most of two of the four ‘branches’ of the MabinogiThe four ‘branches’ are distinct tales that are nevertheless related through the recurrence of certain characters and themes. (a famous cycle of Welsh tales; I am referring to the first and third branches). To condense several episodes in the interests of brevity, Rhiannon appears one day riding a white horse in a forest in Dyfed. The local prince, Pwyll, sees this beautiful damsel while he is out hunting and wants to meet her; he turns his horse towards her, trots, gallops, but can never overtake her, even though her own horse is walking at the same stately pace as before. At last Pwyll cries, “Maiden, [...] for the sake of the man you love most, wait for me!” She stops at once, telling him, “I will wait gladly, [...] and it had been better for the horse if you had asked it long ago.” After this, Pwyll and Rhiannon fall into conversation, get to know one another, and ultimately marry.Pedeir Keinc y Mabinogi, English translation by Patrick K. Ford (1977), The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales, pp. 35–56. The direct quotes are from page 44.

There follows an episode that Patrick Ford calls Cyfranc Caseg a’r Mab, “The Adventure of the Mare and the Boy”, which in his view is closely linked to the story of Macha’s giving birth.Patrick K. Ford (1977), “Introduction”, The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales, pp. 7–8. Rhiannon gives birth to a son, but the baby disappears during the night. Her lady’s maids decide to evade punishment for their negligence by accusing Rhiannon of killing the infant. They sprinkle the blood of a new-born puppy in the room and persist in their false accusation until Rhiannon is condemned. Her sentence is to confess her supposed crime to every traveller approaching their castle of Arberth and offer to carry them on her back into the castle as if on horseback (however, very few people consent to participate in such a degradation). This sentence is to last for seven years, but a year or so later, there arrives at Arberth a certain Teyrnon Twrf Liant with his wife and an infant boy. Teyrnon tells how he discovered the child the night before the May Day in his stable in the district of Gwent Is-Coed, some 150 km east of Arberth: a stable from which new-born foals had been mysteriously disappearing for some years... Everyone recognizes the child as the son of Rhiannon and Pwyll, and Rhiannon is cleared from her unjust sentence.

All of these episodes are in the first branch of the Mabinogi, Pwyll Pendefig Dyfed. In the third, Manawydan fab Llŷr, taking place years later, Rhiannon and her son Pryderi (he whose birth had been attended by such miraculous and tragic circumstances) are among a handful of survivors of a terrible war, along with Manawydan, Rhiannon’s new husband, and Cigfa, the wife of Pryderi. Pryderi and Rhiannon are trapped in an enchanted castle. During her magical captivity, Rhiannon must wear a donkey’s collar.Pedeir Keinc y Mabinogi, English translation by Patrick K. Ford (1977), The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales, pp. 73–87. In sum, the advent of Rhiannon—a ‘great queen’ like Epona and the Morrígan—is signalled by a miracle involving horses. Her son’s birth is complicated by the boy’s disappearance and reappearance in a distant stable. Rhiannon is twice condemned to enact humiliating equine performances.

Liath Macha

According to Ford, “The Adventure of the Mare and the Boy” gave rise to yet another Irish myth, Compert Con Culainn “The Birth (or Conception) of Cú Chulainn”, the champion of Ulster during the invasion of that province by the great army of Medb, Queen of Connacht (the so-called ‘Cattle-Raid of Cooley’). The kingThe king in question is Conchobar mac Nessa, King of Ulster, who flourished according to traditional historiography in the 1st (Lebor Gabála Érenn, Foras Feasa ar Éirinn) or 2nd century BCE (Annals of the Four Masters). and his entourage are hunting a flock of supernatural birds from Slíab FuaitSlíab Fuait, or the Fews, is a stretch of hilly country in Ulster south of Armagh. when a snowstorm forces them to seek shelter. The sole structure they can find is the house of a farmer whose wife is then in labour—as is a mare just outside the door. The latter gives birth to twin foals, the former to the hero Cú Chulainn.In one of the two surviving versions of this tale, Cú Chulainn is only born after an abortion, a reincarnation, and an apparition of the god Lug Lamfada. Patrick K. Ford (1977), “Introduction”, The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales, pp. 7–8. The morning after these births, the house has disappeared along with the farmer, his wife, and the mare. All that remains are the king and his party, the baby, and the two foals.Patrick K. Ford (1977), “Introduction”, The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales, pp. 7–8.

There are several thematic resemblances between the story of Compert Con Culainn and that of Rhiannon in the first branch of the Mabinogi. But, you might ask, what does this have to do with Macha or Epona? Ah, I have omitted to mention the name of one of the horses born that night, namely the Liath Macha “the grey of Macha”, the “king of the steeds of Ulster”Aided Con Culainn (English translation). that would later draw Cú Chulainn’s chariot along with his brother the Dub Sainglenn. Furthermore, Cú Chulainn himself was to prove his prowess, acquire his name, and spend much of his time at Emain Macha, the city founded by Macha Mong Ruad, where Macha the wife of Crunn cursed the men of Ulster—a curse whose consequences Cú Chulainn will seek to counteract during the great Raid by fighting,Cú Chulainn is the only Ulster warrior not afflicted by the curse. The reason why has been disputed: it may be because he is not a man but a demi-god (being the son of Lug Lamfada) or a boy (his beard has not yet grown), or his gender identity may be non-binary, or he may have been born outside of Ulster... often as not, in the chariot drawn by the Liath Macha. The day of Cú Chulainn’s death, the Liath Macha seemed to foresee the tragedy; he wept before, he refused at first to be yoked to the chariot. When Cú Chulainn died, the grey horse protected his body by leading the charge on his own against the enemy. After the battle, the Liath Macha disappeared into a lake in Slíab Fuait.Aided Con Culainn (English translation). In sum, these tales place Cú Chulainn at the centre of a web of mythological associations inextricably bound up with Macha. As Macha is, once again, a person of the triad called the Morrígan (‘great queen’ like Rhiannon and Epona Regina), and the Morrígan herself encounters Cú Chulainn on several occasions during the Táin Bó Cuailgne. She tries to seduce him, she fights him, she leads him astray, she prophesies his victory over the forces of Connacht...Táin Bó Cuailgne. English translation by Ciaran Carson (2008), Penguin Classics, ISBN 978-0-140-45530-4, pp. 92–96, 197. then after his death, she takes the form of a raven to watch over his body.Aided Con Culainn (English translation).

Common themes

One might notice the coincidence of many themes in the mythology of Macha and Rhiannon: the difficult birth of twins in locations more suited to horses; the unexpected advent of a fairy or supernatural woman among mortals; the evil consequences to men for not respecting the woman’s dignity... One may add the close connections with royal power and the constant equine allusions: horseback riding, the birth of foals, the donkey’s collar, the chariot race, etc. Both oversee the destiny of a hero (whether Pryderi or Cú Chulainn) from the moment of his birth, when he is twinned with one or more foals: this theme finds no parallel with Epona, but this may be due to the disappearance of the bulk of Gaulish mythology. Meanwhile, her recurrent links with Hercules may permit us to imagine some parallels...

Conclusions

While Epona is above all the goddess who looks after horses, donkeys, mules, and the people who deal with these animals, such a role leads her to assume further responsibilities as well. Horseback riding is a prestige activity prized by nobles and kings. Epigraphic evidence as well as Indo-European parallels encourage us to perceive a particular role for Epona in royal power and the renewal of sovereignty over the land. But Epona also looks after the fate of the most lowly; she assures the land’s fertility for the well-being of all. And at the moment of death, it may be she who leads their souls into the Otherworld.

Epona has thus been able to extend her role into areas related to her own. This permits us to consider her also as a patron of those machines that have so often been substituted for horses (trains, cars, motorcycles, etc.). One may also re-envision Epona’s role in a political context in which the sovereignty of the land has often been invested in democratic republics.

References

En français svp !

Auf deutsch, bitte!